By Christopher Conway, UT Arlington.

In the middle of the twentieth century, Hollywood was a powerful force in the everyday lives of Mexican moviegoers. The numbers tells the story. In Monterrey, Mexico, in 1932, movie theaters screened 617 Hollywood films to 10 Mexican ones, while in 1952 it was 760 to 161.[1] In Mexico City, between 1950 and 1960, 2,352 American films were shown to 894 Mexican ones. [2] As might be expected, Hollywood Westerns were ubiquitous in the consciousness of mid-twentieth century Mexican moviegoers. They were also prominent in early Mexican television programming. By the mid-1950s, the Frederic W. Ziv Corporation and the Fremantle Corporation were marketing dubbed television Westerns in Mexico and throughout Latin America, most notably The Cisco Kid and Hopalong Cassidy. [3] As Michael Kackman writes, these kinds of distribution deals became a $100 million dollar business that provided up to half of the television programming around the world. [4] Characters like The Lone Ranger and the Cartwright Family from Bonanza were universally known by middle class kids from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego.

Press books, also known as press kits, were booklets or printed and folded tabloid sheets containing graphics, illustrations, promotional texts, cast information, plot summary, and “catch lines” for local print, radio, or television use.

The ubiquity of American mass entertainment in Latin America raises important questions: Are Hollywood film and television archetypes a form of American cultural imperialism? How has American formula storytelling shaped cultural creation in Mexico and other nations? How did American distributors market film and television programs internationally? Although these broad questions are too big to tackle in a brief newsletter article, certain cultural artifacts can provide some insight and get us started. A few years ago, while I was writing my last book, Heroes of the Borderlands: The Western in Mexican Film, Comics, and Music (University of New Mexico Press, 2019), I came across an interesting eBay item that I purchased immediately: the United Artists Mexican press book for The Magnificent Seven (1960). Press books were booklets or printed and folded tabloid sheets containing graphics, illustrations, promotional texts, cast information, a plot summary, and “catch lines” for local print, radio, or television use. I was curious to see how the United Artists marketing campaign tackled the promotion of this iconic film in Mexico, particularly because of how The Magnificent Seven stereotypes Mexicans, and because the film’s production in Mexico involved friction with Mexican censors.

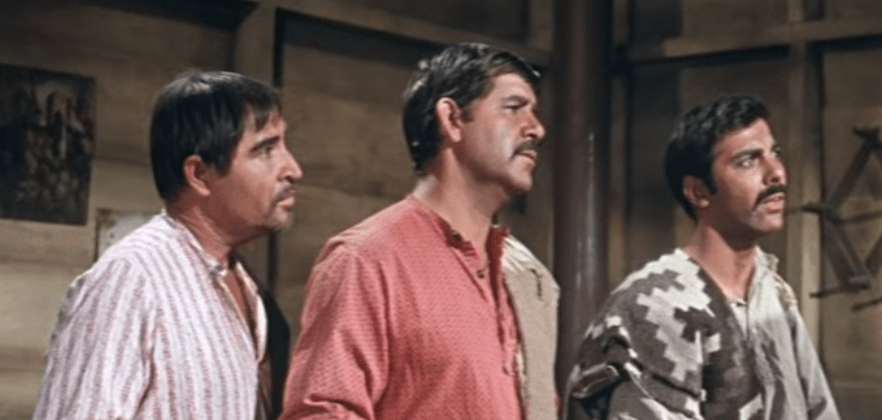

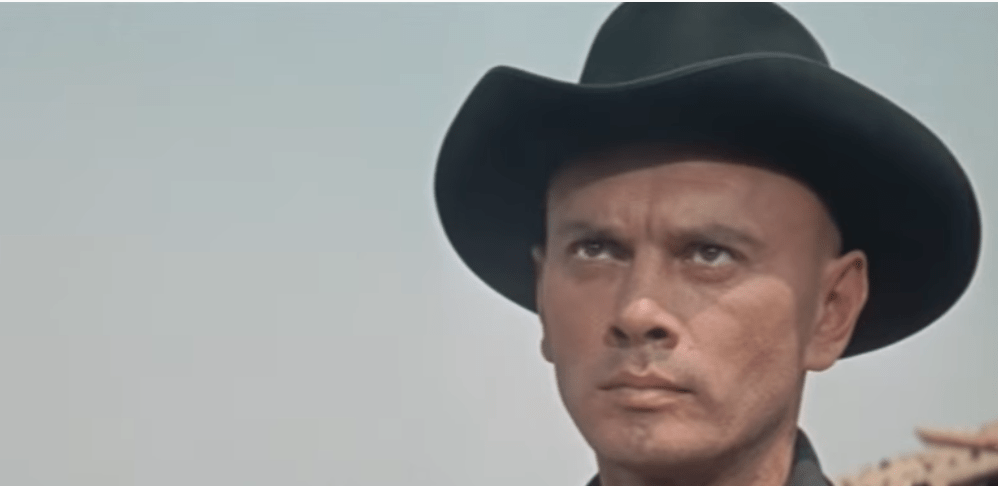

As even casual aficionados of Westerns know, The Magnificent Seven is an adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (1954), a glorious, black and white epic about ronin, or itinerant and unemployed samurais who redeem themselves by defending a village of peaceful farmers. John Sturges’s American adaptation tells the story of a band of seven, down-on-their luck gunfighters who are hired by a village of peasants to protect them from Calvera, a fearsome bandit with an army of villains at his command. The film was not that successful at the box office and critics generally picked at it. Howard Thompson of The New York Times dryly noted that “Japan is still ahead.” [5] Variety’s review complained about an overly busy last third of the film and how the heroes are “too magnificent for comfort.” [6] The problem of the film’s original reception might have related to its unexpected casting, which John Bustin of the Austin American Statesman summarized as follows: “Imagine, if you can, egg-bald Yul Brynner playing an Old West gunfighter, Brooklyn-born Eli Wallach as a Mexican bandit and Germany’s Horst Buchholz as a reckless young caballero named Chico- all in a Westernized version of a Japanese film about 12th century samurai.”[7] But The Magnificent Seven was a hit abroad, it spawned popular, low rent sequels that dovetailed with the rise of Spaghetti Westerns, and over time, it became a beloved classic of the Western genre. Baby Boomer and Generation X readers of this essay will remember that Marlboro Cigarettes picked up Elmer Bernstein’s score and transformed it into the most recognizable advertising jingle of all time.

In his encyclopedic and pointed study of Westerns titled Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (1992), Richard Slotkin analyzes The Magnificent Seven in relation to Cold War politics, culture, and military strategy. He argues that the film “anticipates” Vietnam era strategies and contradictions like the myth of the “surgical strike,” the limits of democracy, deterrence theory, and the paradoxical pairing of technocratic, “professional” killing with sentimental intangibles like honor and chivalry.[8] Slotkin also underlines that the film presents the Seven as a “killer” elite of whites who are unquestioningly superior to their Mexican antagonists. Indeed, when I recently went to see The Magnificent Seven at a revival theater in Dallas, Texas, I was struck by how poorly its cultural politics have aged in comparison to other “classic” Westerns like Red River (1948), Shane (1953) or The Searchers (1956). The passive nature of the Mexican peasants who depend on the Seven, and the “brown-face” performance of Eli Wallach as the bandido Calvera, are hard to ignore and dismiss. Whereas Red River and The Searchers present scenes of racist objectification, they also condemn those acts and beliefs, rejecting the heroic archetype of the individualistic and entrepreneurial Anglo-American gunfighter. Ironically, the making of The Magnificent Seven in Mexico was interrupted by script revisions demanded by the Mexican government, which objected to how the film depicted Mexicans in certain scenes. One concession John Sturges made was to dress the Mexican peasants in clean white clothes to avoid the stereotype of “dirty” or untrustworthy Mexicans. Another was to change the script to clarify that the Mexican peasants who go to the American border town to get help are originally there to buy guns for self-defense rather than to hire American gunfighters. [9] It’s only when they realize how cheap it is to hire gunfighters that they change course and hire men. Mexico also assigned the legendary and fearsome Mexican director and actor, Emilio “El Indio” Fernández, to the production as an Assistant Director. (In the U.S., Fernández is best known as the Mexican General in Sam Peckinpah’s iconoclastic, 1969 Western The Wild Bunch.)

The most interesting article in the press book is titled “A Name To Remember,” which is about a nine-year-old Mexican girl from Tepoztlan named Shirley Temple Velázquez, who appears in the film as a dancing villager.

The Mexican press book for The Magnificent Seven, screened in Mexico as Seven Men and One Destiny (Siete Hombres y Un Destino), contains some of the same elements as the American press book, such as a plot summary, poster graphics and designs, and a generic news article titled in the original English as “The Magnificent Seven Story of Outlaws and Gunslingers” but translated into Spanish as “Bullets, Action, Death, Suspense in Seven Men and One Destiny.” The Spanish language synopsis of the movie, like the American one, demonstrates some hedging about why the Mexican peasants go into town looking for help: the villagers go to the border to “buy guns or perhaps to contract the services of professional gunfighters” (my emphasis.) The Mexican press book contains more Spanish language news articles than the original one, such as “Although You Might Not Believe It, Yul Brynner Stars in His First Western,” or “Seven Men Multiplied by One Hundred,” or “The Use of Numbers in Titles Imply Luck or Magnificence,” which refers to numerology in the French novel The Three Musketeers (1844) by Alexander Dumas and the Spanish novel The Four Men of the Apocalypse (1916) by Vicente Blasco Ibañez. “The number seven is generally considered a lucky number,” the article intones, “whereas thirteen is a number associated with bad luck.” [10] The most interesting article in the press book is titled “A Name To Remember,” which is about a nine-year-old Mexican girl from Tepoztlan named Shirley Temple Velázquez, who appears in the film as a dancing villager. This article, like others in the press book, emphasizes that The Magnificent Seven was filmed on site in Mexico, in Cuernavaca, Tepoztlán, Oacalco, and Mexico City’s Churubusco studios.

“Attention! Yul Brynner, the impeccable actor, dons the costume of cowboy for the first time and goes around armed to the teeth, mercilessly killing those who dare to challenge his infallible trigger!”

The Mexican press book instructs exhibitors about how to stage their street front marquees. The most important instructions are to feature the number seven prominently, and to promote Yul Brynner’s role in the film by placing his photograph in strategic places in the theater’s lobby. The instructions also emphasize Mexican connections: “Mention that many Mexican artists are featured in this production, and that the movie was produced in Mexico.” The Spanish language catch lines United Artists provides for posting in lobbies are also specific to the Mexican press book. One reads: “An all color Panavision production, set in a picturesque region of Mexico, with a star studded cast headed by Yul Brynner, the actor admired by millions because of his manly performances!” Another says: “Attention! Yul Brynner, the impeccable actor, dons the costume of cowboy for the first time and goes around armed to the teeth, mercilessly killing those who dare to challenge his infallible trigger!”

Whereas in the American pressbook Steve McQueen’s television stardom made him a focal point of some of the film’s marketing, he is entirely absent from the Mexican press book except for a group photo of the Seven with their guns drawn.

Although the Mexican press book recycles elements of the American one, and its promotional strategies and campaigns are roughly equivalent (Hold a contest! Use the number 7!), the most salient points of divergence between the press books are evident in the emphasis given to the Mexican locations where the film was shot and the participation of Mexican actors in the film. Although the anchors of the advertising campaigns in both are primarily Yul Brynner, and the novelty and drama of the number “7,” the copy writers and translators at United Artists tried to find some angles to root the film in a Mexican frame of reference.

A more consistent and thorough review of Spanish language press books prepared by American film companies in the mid-twentieth century might offer some insights into some of the advertising strategies deployed to promote Hollywood films in Mexico and Latin America. Equally interesting is how Mexican film companies advertised Mexican films in the Mexican and American markets through their own press books. In my collection of Westerniana I have another press book for an Azteca Films movie titled A Bullet is My Witness (Una Bala Es Mi Testigo, 1960). Azteca Films was an American distributor of Mexican films with offices in Los Angeles, San Antonio, Denver, Chicago, and New York. Their press book offered lobby cards, movie stills, posters, and mats to U.S. movie theaters that served the Mexican and Mexican American community. The company also licensed Mexican films for Spanish language television stations in the United States. Although this press book and my Magnificent Seven Mexican one are fun novelty items, they are also artifacts that underline many of the questions that interest me as a scholar of transnationalism and popular culture. As the study of media and culture moves beyond strictly nationalist categories into the arena of globalization, scholars are beginning to consider items like international press books, posters, movie magazines, and movie reviews to learn something new about cross-cultural communication and miscommunication.

[1] Rendón, José Carlos Lozano, Daniel Biltereyst, Lorena Frankenberg, Philippe Meers, and Lucila Hinojosa. “Exhibición y programación cinematográfica en Monterrey, México de 1922 a 1962: un estudio de caso desde la perspectiva de la ‘Nueva historia del cine.’” Global Media Journal México 9, no. 18 (May 3, 2013). [2] Rendón, José Carlos Lozano, et al . [3] Rouse, Morleen Getz. “A History of the F. W. Ziv Radio and Television Syndication Companies: 1930-1960.” Ph.D., University of Michigan, 1976. [4] Kackman, Michael. “Nothing On But Hoppy Badges: Hopalong Cassidy, William Boyd Enterprises, and Emergent Media Globalization.” Cinema Journal 47, no. 4 (August 14, 2008): 76–101. [5] Thompson, Howard. “Screen: On Japanese Idea:’ Magnificent Seven,’ a U.S. Western, Opens.” The New York Times, November 24, 1960, sec. Archives. [6] Staff, Variety. “Magnificent Seven.” Variety (blog), January 1, 1960. https://variety.com/1959/film/reviews/magnificent-seven-1200419670/. [7] Bustin, John. “Show World: The Magnificent Seven.” Austin American-Statesman. October 14, 1960. [8] Slotkin, Richard. Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America. University of Oklahoma Press, 1998 [9] Wallach, Eli. The Good, the Bad, and Me: In My Anecdotage. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014. [10] United Artists, Siete Hombres y Un Destino (Press Book), 1960.

Christopher Conway is Professor of Spanish in the Department of Modern Languages at the University of Texas at Arlington, a faculty fellow at the campus’s Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, and one of the editors of its newsletter Fronteras. He is the author most recently of Heroes of the Borderlands: The Western in Mexican Film, Comics, and Music (University of New Mexico Press, 2019). Current or forthcoming projects include book chapters and essays on the American West and Southwest, and Latin American comics and graphic fiction.