“The idea is that time can be colonized just like land. By ‘time’ I don’t necessarily mean the length of a day, but the way that the passing of time is experienced and the way individuals relate their current experiences to the past and the future, or even conceive of things like past, future, and continuity.”

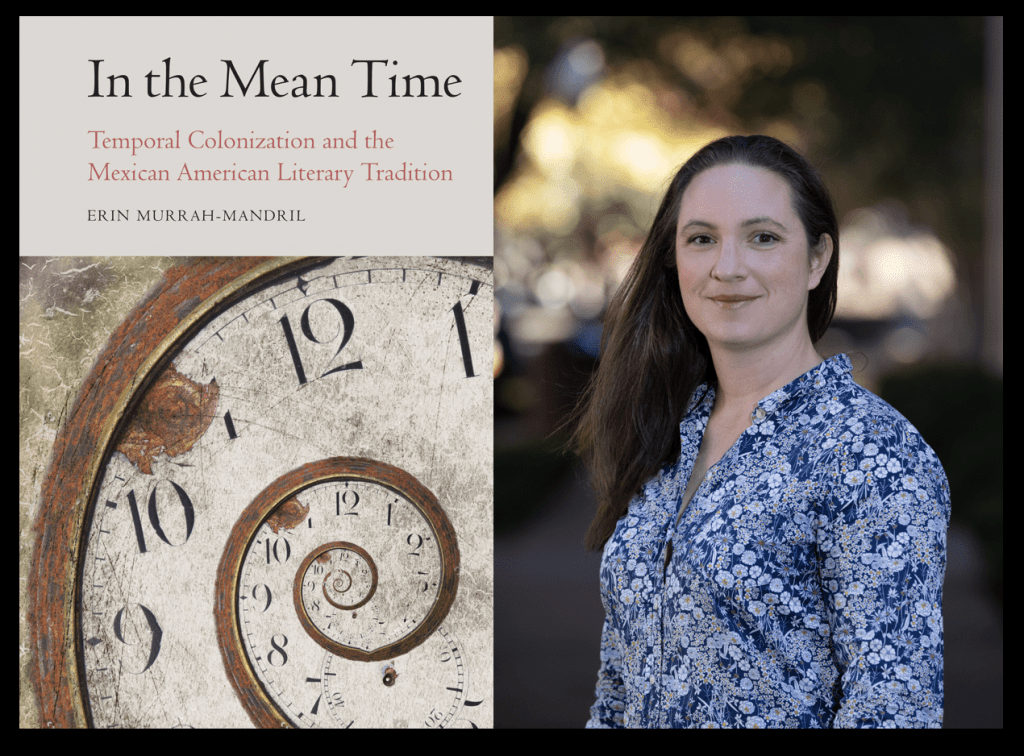

Fronteras: Congratulations on the release of your book, In the Mean Time: Temporal Colonization and the Mexican American Literary Tradition, published by University of Nebraska Press. Can you briefly tell us about some of your book’s key arguments?

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: Thank you. The book has three interrelated arguments. The first is that the U.S. colonization of the Southwest changed the way people experienced time. The idea is that time can be colonized just like land. By “time” I don’t necessarily mean the length of a day, but the way that the passing of time is experienced and the way individuals relate their current experiences to the past and the future, or even conceive of things like past, future, and continuity. The second argument is that Mexican American authors—and I am looking mostly at economically privileged Mexican Americans of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century—navigated the transformation of time during this period by writing themselves into shifting national narratives. Narrative, telling stories, be they fiction or non-fiction, is really a way of organizing time. How did things happen, in what order, how are events related to each other? So, these authors are organizing time in their own way as they tell stories. The third argument is about literary recovery. The authors I am writing about were almost entirely unknown twenty-five years ago even though many of them published books and were well known in their time as writers, business people, politicians, etc. Their writing was discovered and reprinted by scholars in the 1990s. So, this discontinuous history of loss and recovery is part of the story of colonized time and of how Mexican American authors write within that framework.

Fronteras: Time and temporality at first glance seem like elusive and slippery phenomena. Can you tell us about the kinds of cultural materials and interpretive tools needed to define them as objects of study and reconstruct their history?

“My book focuses on the sociocultural aspect of time: how do people talk about time, what metaphors are they using, and how do these beliefs affect people’s lived experience? There are also many material artifacts that shed light on our relationship to time.“

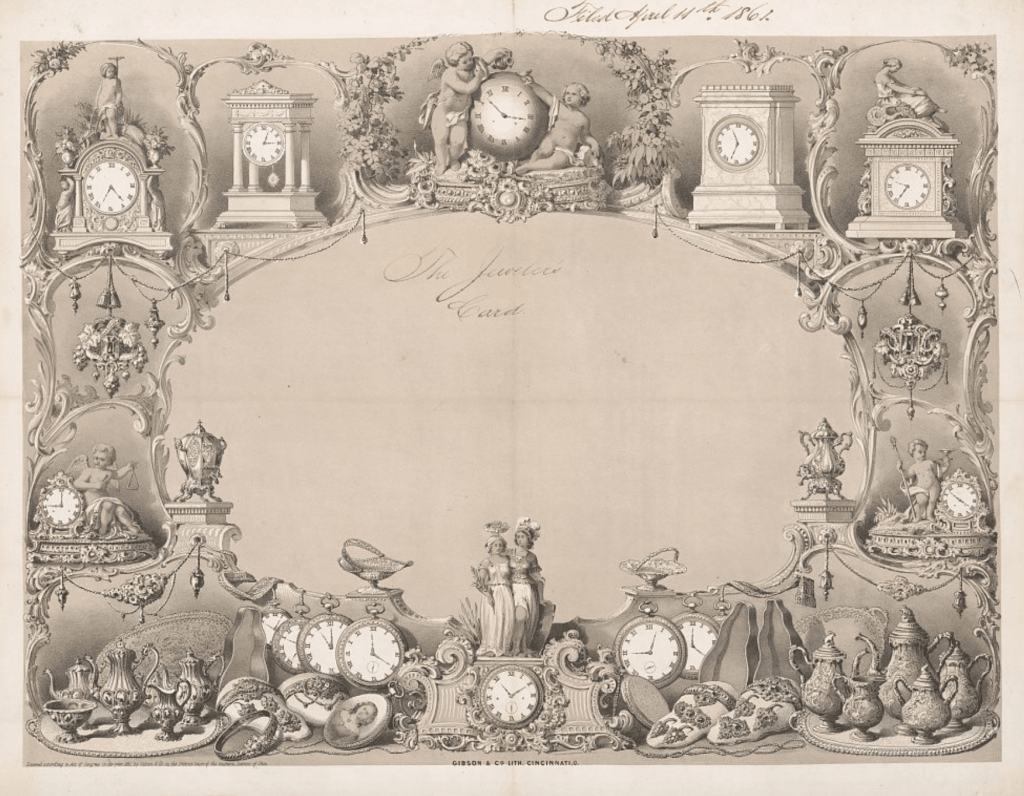

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: Time is difficult to think about because you can’t get out of it. There is no atemporal vantage point from which to examine time. It’s very easy to get lost in philosophies of time, from St. Augustine’s 4th century treaties on time to contemporary theories in physics. My book focuses on the sociocultural aspect of time: how do people talk about time, what metaphors are they using, and how do these beliefs affect people’s lived experience? There are also many material artifacts that shed light on our relationship to time. For example, think about the difference between a community that relies on church bells to mark time vs a community where most people wear a watch. The first is an externalized time that ties the regular ringing of a bell to communal behavior be it vespers or just eating dinner. Wearing a watch is more individualistic, but it also helps the wearer internalize time consciousness. As a commodity, watches have long been a status symbol, showcasing the wearer’s mastery of timekeeping. Think of how people check the time on their cell phones now. I think there’s something to be said for the idea that whatever is telling your time is also, in some ways, controlling your time.

Fronteras: How does In the Mean Time dialogue with scholarly conversations in Borderlands Studies?

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: I draw from Borderlands Studies’ idea that space—something once considered a neutral medium that we just move through—is actually an ideologically imbued social construction. I am also influenced by Chicana and Chicano scholars use of the concept, mestizaje. Mestizaje is rooted in the idea of a combined Indigenous and Spanish heritage, but scholars and other writers in the U.S. have also expanded it to include other kinds of hybridity and a way of existing across cultures. Gloria Anzaldúa is probably the most famous writer to do this in her essay about a new mestiza consciousness in Borderlands/La Frontera (1987). I am learning from these concepts and applying them to ideas of time, which also seems neutral but is largely a social construct. I argue that Mexican American authors reveal a certain hybridity of different forms of time. The Southwest is like a palimpsest of different cultures and different colonizations. You know, Texas is famous for its six flags, but each of those flags brought a different way of keeping time, recording history, conducting business and politics, etc., none of which fully erased indigenous relationships with time and space, much as they tried. Borderlands Studies not only examines space, but also its theories often use spatial metaphors. Emma Pérez’s “third space feminism,” and Chela Sandoval’s “differential conscious” (moving across opposing ideological spaces) are two that have influenced me the most, and I thought, “what if we shift these metaphors to time?” What would “third time feminism” or “differential time consciousness” look like? It turns out, time has a lot to do with concepts of race in the U.S., just like space.

“American authors have been describing New England and the United States as symbols of newness, youth, and exceptionalism from William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation to Ralph Waldo Emmerson’s essays. Even today there is a certain privileging of progress over history within the U.S.“

Fronteras: The first chapter of your book is about The Squatter and the Don (1885), a novel by María Amparo Ruiz de Burton that is foundational to Mexican American literary history. In this part of your book you argue that Mexico’s loss of California in the U.S.-Mexico War resulted in the “temporal colonization” of California and its local inhabitants. What was the Anglo-American concept of time and why was it so damaging to the everyday lives and future prospects of the Californios left behind by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo?

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: First, I want to mention that there are many overlapping ways of thinking about time in 19th century U.S. and Mexico. Both are Western colonial nation states. One of the main critiques in Ruiz de Burton’s political satire is what she calls “retroactive law.” Rather than directly taking Californio land, U.S. land laws worked to invalidate Spanish and Mexican land grants, saying essentially, that the land was never the haciendado’s or the ranchero’s land in the first place. From the Califonio perspective, this is a false remaking of history. Another thing that Ruiz de Burton satirizes, more so in her novel Who Would Have Thought It?, Is the U.S. emphasis on newness and progress. American authors have been describing New England and the United States as symbols of newness, youth, and exceptionalism from William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation to Ralph Waldo Emmerson’s essays. Even today there is a certain privileging of progress over history within the U.S. Ruiz de Burton often recasts this pride in newness and innovation into an uncouth lack of hindsight. The United States’ characteristic youthfulness is revealed to be shallow and self-centered in her political satire.

Fronteras: In another chapter, you write about Miguel Antonio Otero (1859-1944), an important New Mexican governor and writer, whose colorful life included encounters with both Buffalo Bill and Theodore Roosevelt. Your analysis examines the ambiguous ways in which this Mexican American politician and writer challenged and reinforced dominant definitions of modernity. Can you tell us more about this argument?

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: Otero tapped into U.S. tropes of progress and newness, especially the adventurous wild west. He casts himself as a participant in the new economies of the west but also as a civilizing force. Otero believed deeply in the power of progress. His family had strong political and economic ties to the U.S. even before the U.S. Mexico War, and Otero began his career believing that the U.S. would bring political independence and economic prosperity to the territory of New Mexico. Modernity, the form of time that has dominated the world for the past few hundred years, depends on the idea that time moves forward homogenously, that it is the same everywhere. It sounds neutral, (like space), but Western culture promotes specific markers of progress within modernity— technological development, political organization, cultural production—and these are very value laden markers. Otero wanted New Mexico to participate in U.S. modernity as an equal, as a state, specifically, with representation in Congress and a self-elected governor, to move through political processes on pace with the rest of the U.S. He tried to prove that New Mexico was worthy of statehood and thus, co-participation in modernity by highlighting all its markers of modernization. He worked to bring economic investment to the territory, combat political corruption, and he touted its fiscal responsibility, and cultural refinement. Over time, as New Mexico was repeatedly denied statehood, he began to question the federal government’s commitment to progress. Theodore Roosevelt and prominent senators portrayed the territory as backwards and underdeveloped in order to deny it political and economic resources. Otero recognized the irony of the situation and ultimately claimed that the federal government was betraying modernity by creating feudal dependency in its territories. Otero never lost faith in the idea of progress or in many of the U.S. temporal values, but he did stop viewing the U.S. as a source of progress and modernity.

Fronteras: What author, text, or conceptual question surprised you the most in the course of researching your book?

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: There is an important critique in the early conversations surrounding Latina and Latino literary recovery. A number of works were initially described as clearly contesting Anglo American power, and other Latina/o authored texts were valued or devalued for how well they fit this pattern of contestation. In the early 2000s, scholars like José Aranda and Jesse Alemán, began to argue that the contestation paradigm was over simplified because it failed to recognize that many of the authors being recovered also benefited from (Spanish) colonization and retained significant class privilege even though their families experienced land dispossession. I absolutely agree with the critique. What surprised me was how difficult it is to hold onto this complexity while making a sustained argument. I think literary scholars really cherish complexity. It’s right up there with clarity. If you can clearly articulate a complex idea, then you’re a pretty good literary scholar. However, I found myself falling into a dualistic narrative of contestation several times, even as I was trying to specifically make the case that retroactive contestation paradigms are themselves a byproduct of temporal colonization. Thankfully, mentors and colleagues helped me think through those pitfalls. But, I was surprised by how pernicious and pervasive oversimplified dualistic arguments are, and I gained a newfound respect for those initial scholars who managed to change the narrative.

“I think it’s important to embrace the way we are intertwined with our subject matter as authors, and I wanted to follow through with recovering voices that have been largely erased.“

Fronteras: Now that In the Mean Time is out, what else are you working on?

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: I am starting a new project about parteras, or midwives, in the U.S. Southwest during the same period In the Mean Time focuses on, the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. While it is shaping up to be a very different project from the first book, I am trying to practice some of the lessons I learned from In the Mean Time. I think it’s important to embrace the way we are intertwined with our subject matter as authors, and I wanted to follow through with recovering voices that have been largely erased. Parteras are in a triple bind when it comes to making it into the historical record. They deal with birth and women’s sexuality, which has been taboo. As the same time, birth is such a common and universal experience that people in power didn’t find it noteworthy. Lastly, midwives themselves were not always literate, and certainly were not wealthy enough to afford the leisure time to write. Nonetheless, their knowledge of birth and women’s bodies was pretty profound. I am starting to see some linkages between early 20th-century parteras and some of the tenets of Chicana feminism that developed in the last quarter of the 20th century.

Dr. Erin Murrah-Mandril: Thank you for this opportunity. It was a delight to chat about my book with you.