Fronteras: Congratulations on the publication of the book Historical Geography, GIScience and Textual Analysis: Landscapes of Time and Place (Springer, 2020), which you coedited with Francis Ludlow and Ferenc Gyuris. What is GIS and what are some of the ways that your book’s chapters use it to understand historical events and geography?

Charles Travis: Thank you very much. GIS stands for geographical information systems, and is a computer mapping platform which captures, stores, visualizes and analyses what is called ‘geo-data’- which can be any phenomena located on the Earth. In one way, the book employs GIS as a hermeneutic tool to explore historical events by the juxtaposition of cartographical techniques and document analysis. The book also aims to provide a rapprochement between the narrative dimensions of historical investigation, and more positivistic approaches in the geosciences.

Fronteras: We want to ask you about the opening chapter of the book, titled “Ghost Cathedral of the Blackland Prairie: Waxahachie, Texas, Places in the Heart, and the Superconducting Collider,” which you coauthored with Javier Reyes. One of the conceptual foundations of the article seems to be that a place cannot be defined or understood outside of its representations, measurements, and data visualizations. Is this a core assumption in all of your work as a cultural and historical geographer?

Charles Travis: I don’t know if the chapter makes such an absolute claim; what it does convey to my mind is that representations, measurements, and data visualizations can supplement personal experiences of a place. Such supplements provide the means for people to conceive in certain cases how places are often palimpsests resting on sedimentary layers of cultural and environmental agency.

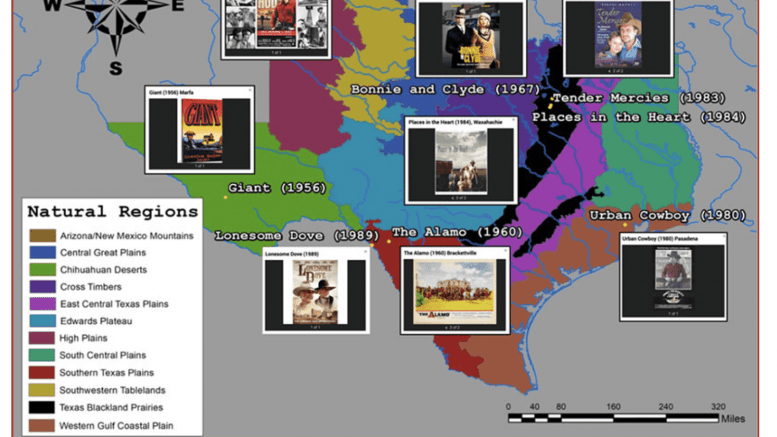

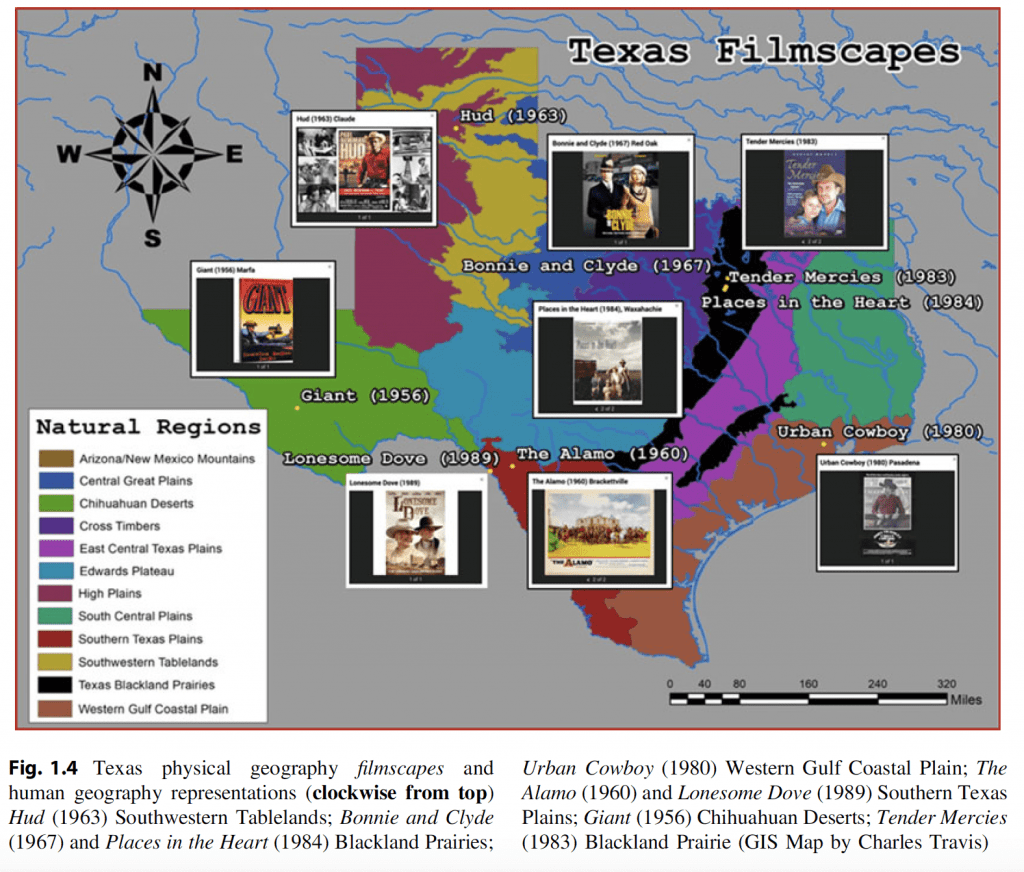

In many ways film is the ‘post-modern’ cartographical medium of our time. The history of cartography suggests that many of the maps were imperial, or commercial projections of the map-maker or cartographer’s culture. In our era, film seems to be adhering to this as well- albeit on several other dimensions.

Fronteras: The article about Waxahachie proposes that film works as an “archive” of discourses, imagery, and metaphors that construct and maintain a sense of place. In turn, films dialogue with other historical artifacts, such as literature and urban or engineering plans. Can you tell us more about how you see film in relation to the study of Texas, and what Places of the Heart (1984) in particular can teach us about Waxahachie as a place in time?

Charles Travis: In many ways film is the ‘post-modern’ cartographical medium of our time. The history of cartography suggests that many of the maps were imperial, or commercial projections of the map-maker or cartographer’s culture. In our era, film seems to be adhering to this as well- albeit on several other dimensions. I had been a fan of Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart long before I set foot in Texas. My PhD concerned a literary geography of Irish writers in the 1930s, and I was always interested in writers and their narrative dimensions of place creation and representation. The film provides a view of the ‘sense of place’ of Waxahachie during the Great Depression from the perspective of Robert Benton’s memory and stories. I think it is the ‘sense of place’ evoking ‘magic’ of storytelling that is important- a craft that another Texas author, Larry McMurtry, laments the loss of in Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen (2010)

Fronteras: We were fascinated by this essay’s treatment of the plan to bring a Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) to Waxahachie in the 1990s. Although the infrastructure and apparatus for this plan was scuttled in 1998, the government project left geological traces behind in the physical landscape through the boring of tunnels under Ellis County. In turn, these events inspired a science fiction novel and brought a production company to the tunnels to film a science fiction movie. It would seem that these events and surprising associations set Waxahachie apart, literally and symbolically, from other Texas cities. Would this be correct? Is this what drew you to Waxahachie?

The place-name Waxahachie itself had a strange attraction to me, and incantatory effect. It was the name that set it apart for me. So it was a collective pull formed by Benton’s film, Javier’s project, and I suppose the great bowl of the sky over the plains on my way down from Arlington last spring that drew me to this ‘Chautauqua’ in north-east Texas.

Charles Travis: Actually, it was my GEOG 4330 “Understanding GIS” student Javier Reyes who called my attention to the SSC in Waxahachie- which was as I understand it, his home town. He mapped the SSC for his course project- and this drew my attention as in the back of my mind, I had planned to conduct a literary and cultural geography exploration of Robert Benton’s depiction of Waxahachie. This led to our collaboration on the Springer book chapter. My investigations led me to go and ‘case-out’ Waxahachie last May, and I also discovered that actually two books had been written about the SSC (the other being by Herman Wouk titled A Hole in Texas). The place-name Waxahachie itself had a strange attraction to me, and incantatory effect. It was the name that set it apart for me. So it was a collective pull formed by Benton’s film, Javier’s project, and I suppose the great bowl of the sky over the plains on my way down from Arlington last spring that drew me to this ‘Chautauqua’ in north-east Texas. In some ways entering the historical part of town was like being in a Brigadoon version of 1930s America, with the name Waxahachie conjuring an indigenous deep-time past.

Fronteras: Can you tell us more about your current and ongoing research projects?

Charles Travis: I am currently working on a book which will be published by Indiana University Press that is tentatively titled Deep Wests. I’ll be employing hermeneutic GIS and literary geography to map and explore the imagined, historical and speculative American west through the lenses of spatial historiography, western fiction, LA Noir and Science Fiction. Those are my plans for the summer of 2020!