Fronteras is delighted to share with its readers this interview with Dr. Joel Deshaye, an Associate Professor of Canadian literature at Memorial University in St. John’s, Canada. His work has appeared in national and international journals, including Canadian Poetry, Canadian Literature, The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, The American Review of Canadian Studies, and The Journal of the Short Story in English. He is the author of The Metaphor of Celebrity: Canadian Poetry and the Public, 1955-1980.

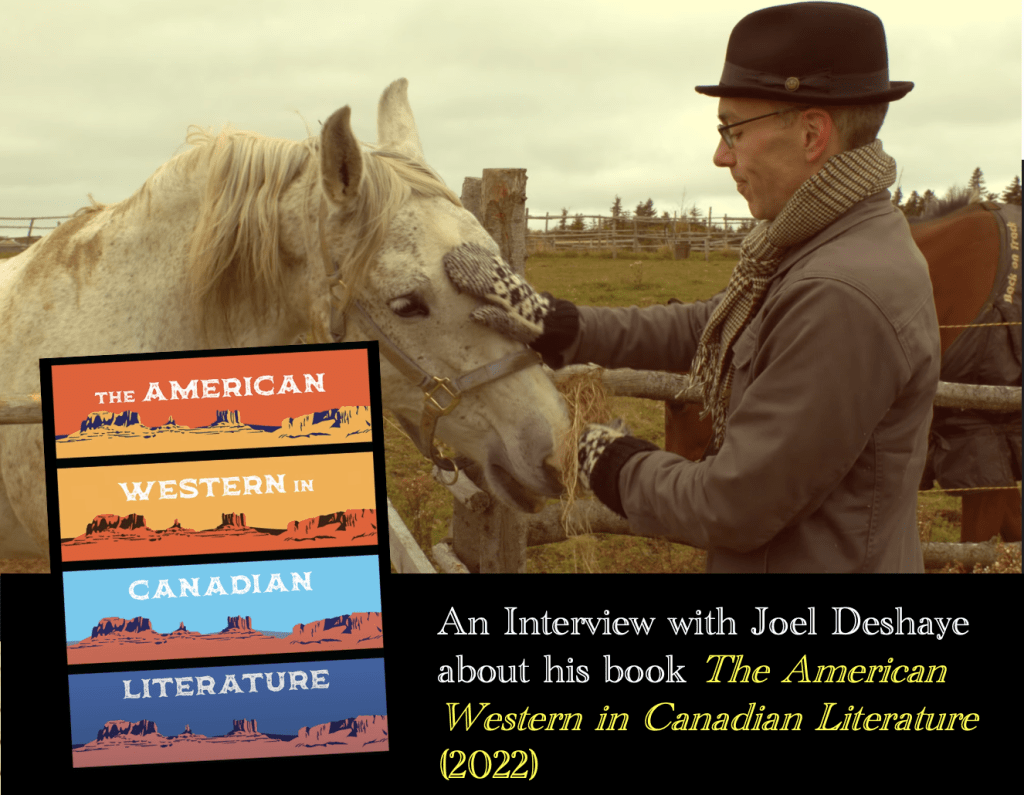

Fronteras: Congratulations on the publication of your new book, The American Western in Canadian Literature (University of Calgary Press, 2022). What was missing from conversations about Canadian Westerns that you wanted to address?

Joel Deshaye: Thanks! I’ve been writing The American Western in Canadian Literature for a decade—in fact, I just realized that I’m implying that it’s still in progress rather than hot off the press. It has been a big job. When I started it, there was established regionalist scholarship on Western literature in Canada, but not much on the Western as a genre. Candida Rifkind and later Christine Bold and Katherine Ann Roberts produced some very interesting studies, and when I could not find many more I went off on a double tangent. First there was transnationalism and the Western, which led me to Stephen Teo’s book Eastern Westerns (2017), which in turn helped to contextualize some of the less directly relevant material that I was working with, stuff like Arjun Appadurai’s Modernity at Large (1996). Second there was regionalism. It was partly regionalist scholarship, which I learned from books by Herb Wylie and Alison Calder among others, that helped me to see the social and political relevance in all the Canadian Westerns that were appearing. Westerns by Canadian authors were appearing more and more often—or at least Western-like texts were, including the type that Neil Campbell and other people associated with the University of Nebraska Press describe as “post-Westerns.”

I had taken a course taught by Guy Vanderhaeghe when I was an undergrad; he wrote a Western set partly in California and partly in Saskatchewan called The Englishman’s Boy (1996), plus two sequels, so Vanderhaeghe was in the back of my mind when I started noticing how often contemporary Canadian writers were addressing or revising the Western. I list a lot more in my book, but the ones I focused on were Vanderhaeghe, Thomas King, Michael Ondaatje, Robert Kroetsch, Paulette Jiles, George Bowering, Gil Adamson, and Patrick DeWitt, others too. I wanted to know what these writers were doing, and why so many were committing time and effort to writing genre fiction, which hadn’t entirely been legitimated as literary—or had been, with earlier writers such as Ralph Connor, before it lost its shine. One reason for the rise and fall of the Western is politics, and though I’m no political scientist I wanted to contextualize Canadian Westerns with politics and the little bits of Canadian and American history that would help us to understand why Canadians and border-crossing Americans like King and Jiles and DeWitt would invoke the United States so prominently. It’s not only that American pop culture is dominant in Canada, but that’s part of it. It’s also partly about different approaches to imperialism. I wanted to understand that cross-border relationship better.

The problem is the distortion of history—the assumption that Native Americans have been conquered and destroyed—that comes out of Hollywood.

Fronteras: Your first book was about Canadian poetry and the concept of celebrity. In this book you return to the topic of celebrity in relation to Hollywood culture and indigenous creators. What are some examples of how indigenous writers and creators have interrogated and reinvented celebrity Hollywood culture and myths associated with Westerns?

Joel Deshaye: Since you’re noticing the Indigeneity and celebrity connection, the main example is definitely Thomas King and his novel Green Grass, Running Water (1993). I’m guessing that a lot of your readers will know his name, because he was born in California into a partly Cherokee family. After moving to Canada, he gained international attention for his many novels, including some more obvious forays into genre fiction with his series of crime novels. As I understand it, King’s novel takes issue with many of the evils of colonization, but, surprisingly playfully, he then looks to the Westerns of John Wayne. Green Grass, Running Water features a wildly imaginative scene where several Indigenous spirits jump into a Wayne movie that’s on TV. They rewrite the standard plot of Wayne’s triumph in the “cowboys and Indians” battle so that Wayne is the one who is killed. I thought about that for a long time. I think that King was taking issue with what Wayne represented and still represents: the colonial figure whose respect for Indigenous people was pretty tokenistic in a movie like John Farrow’s Hondo (1953), which was based on a Louis L’Amour story. The problem is the distortion of history—the assumption that Native Americans have been conquered and destroyed—that comes out of Hollywood. I don’t know Indigenous literatures well enough to have lots of related examples, but in Canada there are prominent ones like Jordan Abel’s first two books, which took 10,000 pages of American Westerns from the public domain and condensed and re-wrote them from an Indigenous perspective. There’s also the example of a direct response to John Wayne’s film The Searchers (1956), a recent film—from 2016, I think—called Maliglutit made up North by Zacharias Kunuk and Natar Ungulaaq. The word “maliglutit” means “searchers” or “followers” in Inuktitut. In the film, the basic plot of The Searchers remains the same, but the conflict is between neighbouring communities and not white people, and guns are used so sparingly that they take on some really interesting and unusual symbolic dimensions partly related to Inuit mythology. So that’s another example of a direct Indigenous response, in Canada, to the Western.

In the United States, there are examples like Louise Erdrich and Sherman Alexie who also offer Indigenous responses to Wayne. In terms of cowboys more generally, I’d also like to mention Garry Gottfriedson, a poet in British Columbia who takes an approach to Westerns that tries to balance their problems with the appeal of ranch-land to Indigenous people in modern times.

There was one that I read too late to be able to mention in The American Western in Canadian Literature: Marvin Francis’s City Treaty (2002). City Treaty is a funny, very smart book that comments several times on Westerns. It’s about how cities are on Indigenous lands according to the treaties between the Canadian government and various First Nations, even if the related system of reservations was meant to push Indigenous people out of urban areas. That’s a point I could have made in my book: that the zones of contention in the Western don’t only gravitate North, but they also gravitate to cities, sort of like how Clint Eastwood’s cowboy modernized into Dirty Harry, a cop in San Francisco. So one of the myths reinvented here is that the Western can only be found in the rural America of the Old West, when it’s been moving in Canada and elsewhere for more than a century.

Fronteras: Fans and commentators of American Westerns tend primarily think about the geography of Westerns in terms of East vs. West. In the case of Canadian Westerns, there is also the north. What is the Northwestern Western and how does it differ from other kinds of Westerns?

Joel Deshaye: Yes, and in fact I’d say that the North is important in American Westerns too. The subgenres of the closely related Northern and the Northwestern emerged conceptually in response to American expansionism around the time of the Alaska Purchase in 1867. As examples in print, I consider turn-of-the-century novels by Ralph Connor, like Black Rock (1898) and Corporal Cameron (1912), that were basically Westerns set mostly in northern parts of Canada, and by that I mean not really that far north (not into Inuit territory) but into less hospitable climates. In Pierre Berton’s very readable book Hollywood’s Canada (1975), Berton claims that there were hundreds of B-list American Westerns on film, and some A-list examples, that are set partly in Canada, where Canada becomes a new frontier. The subgenre indirectly exposed a lot of the problems with the idea of the frontier, because suddenly the frontier encroached on another nation-state, not “only” (in quotation marks) Indigenous lands. Of course, that’s not something that you tend to see in Northerns or Northwesterns themselves, where there’s just the novelty of a different backdrop to the same story. Or, as my friend and colleague Andrew Loman joked to me, maybe it’s a new “foredrop” because the scenery is so much in the foreground of Westerns and other regionalist texts.

Fronteras: In more than one part of your book you explore the ways in which popular culture flows across the U.S. Canada border, resulting in critical reimaginings of the Western. One example you foreground is the case of Canadian pulp literature. What kinds of exchanges do you see at work in Canadian pulps that might be revealing for an understanding of Canadian literature or how popular genres work writ large?

Joel Deshaye: Westerns in Canadian pulp fiction and comics are not my main area of study, but I had to jump into them for the sake of the historical scope and continuity of this project, and I learned that they were mainly a phenomenon of the Second World War. Canada has always had the economic problem, sometimes called a “brain drain,” of bigger markets in the United States that draw talent south and export final products north. Our copyright laws have not always kept pace with that reality, as scholars such as Eli MacLaren have shown. In terms of comics, during the war Canada imposed laws on imports to redirect resources (in theory anyway) to the war effort. At the time, the Canadian disposable income that was spent on cultural commodities was mostly spent on American imports like movies, comic books, and books. This was partly because American companies had bought up Canadian cinemas in the early years of film as a mass medium and thereafter stopped playing Canadian films. Actually, I don’t know for sure that Canadians were screening many Canadian films then; maybe they were already mostly American. But on the assumption that the government could divert money into its own coffers and thereby have more to send to Britain, suddenly American Westerns were effectively illegal in Canada, and some companies started up in Toronto to take over the market. I write about this in a chapter I contributed to Christopher Conway and Antoinette Sol’s The Comic Book Western: New Perspectives on a Global Genre (2022). What I don’t write about in that book but only in The American Western in Canadian Literature is a pulp fictional example, not a comic, by a writer known as Luke Price. Price was writing in the Canadian magazine Dynamic Western. One of the “exchanges” that might be at work there is that Luke Price could be an American looking for a way into the new market in Canada. I tried to find a record of him, or her, or they, but so many pseudonyms were in use in pulp fiction that there’s a good chance “Luke Price” is not Luke Price. Issue after issue, Price’s stories add up like a novel to present a character named Smokey Carmain, a duelling sheriff in the American Southwest who does everything you’d expect a duelling sheriff to do in the genre: ride a horse and fight and shoot and tip his hat to the ladies. It appeared that Price was really working up to something like character development even in a genre and format that are still famous for flat, one-dimensional characters. But then the war ended, the laws changed, and television took over. The market for Westerns in pulp fiction and comics in Canada shrank dramatically, partly because of TV.

Another part of my critical framework is simply postmodern genre-bending, which, now that I think of it, really shaped my entire book, from contemporary Indigenous responses all the way back to Ralph Connor and HA Cody and their crossover novels for multiple audiences.

Fronteras: You link conversations about gothic or phantasmagoric dimensions of some westerns to the topic of postmodernism. Can you share an example of a gothic or phantasmagoric moment in a Canadian Western and how you frame it critically in your book?

Joel Deshaye: Basically, “ghostmodernism” is gothic postmodernism, or postmodernism with ghosts. It was an idea that I was developing based on a coinage from a Canadian professor, Sylvia Soderlind. In The American Western in Canadian Literature I work through the idea with examples from Michael Ondaatje and Paulette Jiles. Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1970) can be read, as Ian Rae and others have suggested, by a Billy who is shot by the sheriff Pat Garrett but then relives his life from a weird perspective, maybe a movie camera, maybe a ghost. It’s subtle, strange, really wonderful. Something similar happens in Jiles’s The Jesse James Poems (1988), where halfway through the book Jesse James is murdered but he and his gang live on beyond the moment of death. Part of the critical framework for these examples goes back to your earlier questions: it’s about celebrity or legend living on, creating an afterlife. Writers of postmodern literature and theory seem to be inspired, too, by how popular culture drives this sort of life-to-death-and-life-again recycling. In these examples, ghostmodernism literalizes the metaphor of the post-Western that Neil Campbell writes about. For Campbell, post-Westerns are all about how non-Western or Western-like texts that exist in the pop-cultural shadow of the Western are “haunted” by Westerns. Another part of my critical framework is simply postmodern genre-bending, which, now that I think of it, really shaped my entire book, from contemporary Indigenous responses all the way back to Ralph Connor and HA Cody and their crossover novels for multiple audiences. Funny how some of this isn’t so obvious until someone asks you about it!

Fronteras: One of the ways you explore major Canadian Westerns by Guy Vanderhaeghe and Gil Adamson is to propose the concept of “Degeneration through violence,” which revises Richard Slotkin’s well known concept of “regeneration through violence.” What do you mean by “degeneration through violence”?

Joel Deshaye: The American poet and scholar Thomas Heise, who taught for a while at McGill University in Montreal, told me to read Richard Slotkin years ago when I was a student, and Slotkin’s work became a touchstone for my own. On a basic level, I’m using his theory of regeneration through violence by flipping it, partly in the context of postmodernism, toward degeneration through violence. Canadian society, which is certainly far less deadly to its own self-identifying members than American society is, sees violence more as a problem—a degeneration—than a solution. I can’t say this without also admitting that colonization was accomplished partly through the very real genocide of the Beothuk in Newfoundland and later cultural genocides as Canada’s own frontier moved into the West. Canada has no purity to speak of. It is not a non-violent society. But, insofar as comparison is meaningful when things might be incommensurate, I started noticing how contemporary Canadian Westerns by Vanderhaeghe, Adamson, and Patrick DeWitt all had these scenes where human violence was met with debilitating responses from nature: disease, disaster, disfigurement. As my book approaches its conclusion, it becomes more and more ecocritical, and the notion of degeneration through violence raises questions about our relationship with nature, partly the land and partly animals such as horses. The Western has been called “horse opera,” after all, so the horse is obviously a central figure of the genre. The last couple of chapters ride off into broader cultural territory of how horses are represented and what they mean in a posthuman context. That classic image, the silhouette of the cowboy on the horse with the sunset behind him—that’s an image of posthuman fusion. I had some fun with that.

I’m glad to see academia’s growing respect for creativity in research, which probably comes out of the institutionalization of creative writing programs. Although it’s also part of a deeply concerning shift towards more commodity-oriented research, the creativity definitely helps with public engagement and the realization of education’s public interest.

Fronteras: What can you tell us about the excellent short film you produced with Jamie Skidmore about your book, titled “Sites of the West in the East (and the Remaking of the Western),” which is available on YouTube. There’s more talk among academics recently about “research-creation” as a supplement to only working in traditional scholarly modes.

Joel Deshaye: Yes, I’m glad to see academia’s growing respect for creativity in research, which probably comes out of the institutionalization of creative writing programs. Although it’s also part of a deeply concerning shift towards more commodity-oriented research, the creativity definitely helps with public engagement and the realization of education’s public interest. Jamie had an ambition to make a film for every researcher in my department, but I think we discovered that the films are very time-consuming to make. But a relatively “quick win,” so to speak, was how the music came together. I’m a rock and jazz musician, so I tried out the genre of Western swing and had some fun with that too.

Fronteras: Thank you for talking with us. Besides promoting your book now, what other projects are you looking forward to developing?

Joel Deshaye: Long story! I have a dataset, in fact, from my study of the Canadian Western: a multi-book index that allows me to search rapidly for Western conventions, such as the cowboy or the horse or the gun, through most of the books that inform the study. The point was to enable distant or surface readings to widen the scope of the project. I ended up cutting most of that material from my book because having to explain the methodology felt like a distraction. So I’m working on an article on representations of landscape that will make use of the dataset more explicitly and in a digital humanities and distant-reading framework. I had done some literary and linguistic computing as a grad student during and after my Master’s degree, way back, so it’s not entirely new to me. There might even be charts!

From that point on, I’m starting a new book project that comes out of the environmentalist finale to my book on the Western. I feel strongly that even more of us need to do work that addresses the root problems, the conceptual problems, of our climate crisis—not only that, but also plastic pollution, habitat loss, the slap-in-the-face warnings of extinctions of other species…. So my new book project is on the problem of the environment being only a metaphor in media ecology, and one partial solution: a more environmentally aware acoustic ecology, a way of thinking that helps us to listen to the land and not coincidentally to the people who have the closest sustainable connections to the land. That’s the theoretical framework, and I’m applying it by reading contemporary Canadian poetry for representations of media in nature, including Marvin Francis; I already mentioned him. He has this brilliant moment in City Treaty where he says that the land is the origin of language, and then he uses a metaphor of modern technology by saying that Indigenous languages need an alarm system and insurance. So we can infer that the land is also at risk if the languages that come from it are at risk. I have a lot of examples to work with from a diverse set of Canadian poets, and I’m looking forward to spending time with that project on non-teaching days this year.

Image credit: Cover tile designed by Christopher Conway. Image from Deshaye and Skidmore’s Sites of the West in the East used with permission.