Dr. Sam W. Haynes is a professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington and director of UTA’s Center for Greater Southwestern Studies. His publications include the books Unfinished Revolution: The Early American Republic in a British World (2010), James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse (1996), and Soldiers of Misfortune: The Somervell and Mier Expeditions (1990).

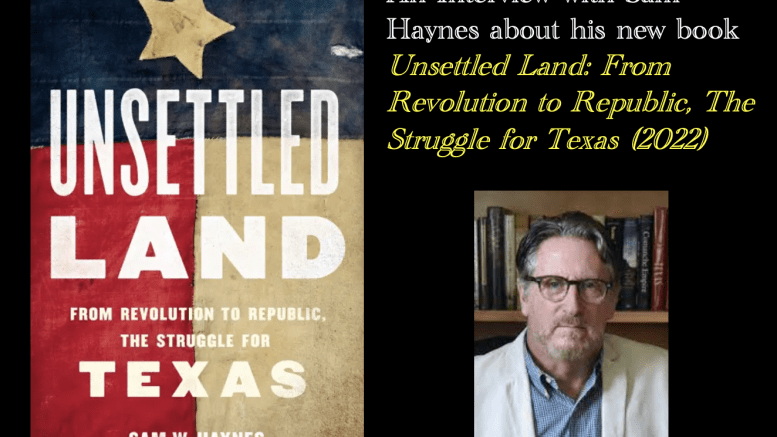

Fronteras: Your book Unsettled Land: From Revolution to Republic, The Struggle for Texas (2022), dismantles the mythical discourse central to nationalist and traditionalist accounts of Texas history by foregrounding the experiences of the Hispanos of Texas (later labeled Tejanos), various indigenous tribes such as the Cherokee and the Comanche, Mexican officials and soldiers, notable enslaved persons, and free Blacks like William Goyens of Nacogdoches. What does this wider and more inclusive lens allow us to understand about Texas that we did not know before?

Sam Haynes: It’s no secret that the traditional narrative of the birth of early modern Texas is an Anglocentric one. It’s a story that has been told almost exclusively by whites, and given the academic stamp of approval by Anglo historians and popular writers for more than a century. As a result, although Texas was one of the most diverse regions in North America, we’re still fixated on a version of events that places a handful of Anglo alpha males at the center of the story. Thus we think of the Revolution as a gripping saga in which outsized figures, all white males (Houston, Crockett, Travis, et. al.), crowd the stage, elbowing aside everyone and everything else. Some newer works have challenged this celebratory narrative (most notably last year’s Forget the Alamo), by pointing to the economic motives of the slaveholders who took up arms against Mexico. But even a critique of the familiar Texas story doesn’t fundamentally alter the way we look at these events. We’re still hostage to a narrative dominated by Anglo-American actors.

What I wanted to do in Unsettled Land was tell a very different story, one that examined a multiethnic Texas during this period, with all its many moving parts. At the outset, I naively assumed that this was simply a matter of inserting people of color into the story. But I quickly realized that you just can’t shoehorn the experiences of other peoples—Hispanos, Native Americans, and people of African descent—into a narrative that is really only interested in highlighting the heroic exploits of white alpha males. Each of these groups has a story to tell, one that needs to be examined separate and apart from the Anglo-Texan experience. So the finished product was more than an attempt to revise the standard narrative. Instead, I wanted to dispense with it entirely, as if telling the story of the birth of early modern Texas for the first time.

I definitely think we’ve overestimated the importance of Stephen F. Austin, the “Father of Texas.”

Fronteras: Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston are arguably the most iconic “foundational fathers” in traditional accounts of Texas history. Rather than tear them down as individuals, your book suggests that they were somewhat irrelevant in comparison to other historical forces and actors that opposed the building of a more just multiracial society. Is that an accurate description of their ability to affect change and events when they were alive?

Sam Haynes: I definitely think we’ve overestimated the importance of Stephen F. Austin, the “Father of Texas.” He was the most successful Anglo colonizer, to be sure, but it’s important to remember that Native American refugees from the United States were coming to Texas, and in the beginning in far greater numbers, when Austin established his colony in the Brazos River valley. As a colonizer, he certainly deserves credit as a skillful diplomat who tried to build bridges between Mexican officials and Anglo-American settlers. But as I argue in the book, Austin became less relevant as the American population grew. Most migrants from the United States never took their obligations as Mexican citizens very seriously, if at all. As the province moved toward open rebellion in the early 1830s, leadership of the white community passed to a group of men who were less willing to compromise with Mexican authorities, men like Brazos planter William Wharton. When Austin returned to Texas on the eve of the rebellion after his lengthy imprisonment in the Mexican capital, he found himself swept up in events he was powerless to control.

Houston is a different case altogether. It’s not an overstatement to say that he was the only prominent Texan who opposed the forced removal of the Cherokees and the immigrant tribes, and he wasn’t afraid to say so, a position that infuriated his enemies and embarrassed his friends. And he repeatedly came to the defense of Texas Hispanos, who were also subject to discrimination and oppression after 1836. But in the end, there was only so much even a popular president like Houston could do in a country whose citizens were defiantly and unapologetically committed to the ideology of white rule.

Fronteras: When most people think of Texas independence, they probably think of San Antonio, because of the outsized myth of the Alamo. However, your book shines a spotlight on the east Texas town of Nacogdoches, to illustrate how pre-Independence Texas was defined by a surprising coexistence of political interests and ethnic groups. Is it fair to consider Nacogdoches a kind of microcosm of how Texas went from being an “unsettled” space of potentially viable multiculturalism to a region defined by Anglo domination and exclusion?

Sam Haynes: Nacogdoches hasn’t received nearly as much attention in the traditional narrative as it deserves, perhaps because it’s much easier to think of Texas as a place of ethnic enclaves, like the American community of San Felipe de Austin and the Mexican community of San Antonio. Nacogdoches was unique—a small town of Mexicans, Anglo-Americans, French creoles and free blacks, many of whom had close economic ties with the many immigrant Indian tribes who lived nearby. The town is really a microcosm of Texas’ multi-racial character during its fifteen-year existence as a province of Mexico. And, for that very reason, it experiences the most dramatic change after independence. Most of Nacogdoches’ Mexican residents flee after the Córdova Rebellion in 1838, and the following year President Lamar drives most of the immigrant Indians out of East Texas. By the time Texas joins the Union in 1845, Nacogdoches is just one of the many towns on the western edges of the American South trying to cash in on the cotton boom.

Fronteras: Chief Bowls of the Texas Cherokees is ultimately a tragic figure in your book, exemplifying the betrayal of the Cherokee by both Mexican and Anglo-American negotiators. Yet your portrayal of him reveals that he was a complex and resourceful politician. Can you tell us a little about him, and the ways that he tried to negotiate the crosscurrents of Mexican and Anglo interests?

Sam Haynes: Complex and resourceful, yes, but ultimately unsuccessful. The fate of the Texas Cherokees is certainly one of the more poignant narrative threads that I follow in the book. Bowls came to Texas in 1819, and spent the next two decades trying to secure legal title to the land the tribe occupied in East Texas. Local and federal authorities were, by and large, sympathetic to the immigrant Indians, but the wheels of the Mexican bureaucracy turned slowly, and by the time the revolution broke out the Cherokees were still squatters with no legal right of ownership. A frustrated Bowls signed a peace treaty with the Anglo rebels, allowing Sam Houston to focus on Santa Anna’s advancing Mexican army. There’s no doubt that the tribe’s decision to remain neutral helped ensure a rebel victory at San Jacinto, but it failed to accomplish the goal of a permanent Cherokee homeland in the Piney Woods. Once independence had been won, the Texas Senate refused to ratify the agreement, and the forced expulsion of the Indians soon followed. In the end, Bowls died fighting Lamar’s ethnic cleansing policy, a far more violent form of Indian removal than anything the Cherokees experienced in the United States on the Trail of Tears.

Fronteras: Your portrait of the Mexican military official Manuel de Mier y Terán, whose analysis of the Texas problem was clear-eyed and prescient, seems sympathetic in comparison to other historical figures. What set Mier y Terán apart from his Mexican contemporaries?

Sam Haynes: Mier y Terán is a Cassandra-like figure, who tried without success to raise the alarm about American immigration in Texas. In part this was due to Mexico’s chronic instability. Much like the Cherokee question, an effective, long-range policy to block the unrestricted influx of Anglo-Americans and their slaves was difficult, if not impossible, for a national government wracked by factionalism and political intrigue. What made Mier y Teran’s inability to stop the Americanization of Texas especially tragic, though, was that he encountered so much resistance from prominent Mexican leaders–men like Lorenzo de Zavala and José Antonio Mexía, who had invested heavily in Texas lands, and who stood to profit from American settlement in the region. Zavala and Mexía deserve no small share of the responsibility for Mexico’s failure to keep Texas from falling into American hands.

Texas attracted more than its fair share of what I call the “adventurer class”—men who believed they could advance more quickly in a new country than in the United States. And to a large extent they were right.

Fronteras: In more than one passage, your book underlines the disorganization, grandstanding, ineptitude, inconsistency, and cruelty of many Texas leaders and soldiers at various turning points. Was this culture of hyper individualism and machismo a product of the hardship of the “frontier” experience, or of other factors specific to the life and politics of Texas?

Sam Haynes: Actually, I think it has more to do with the manic ambition that consumed many white American males during the Jacksonian period. Texas attracted more than its fair share of what I call the “adventurer class”—men who believed they could advance more quickly in a new country than in the United States. And to a large extent they were right. A future president of the Lone Star Republic, Mirabeau Lamar, arrived in Texas as a common private in March 1836. By April he was a colonel in Sam Houston’s army, and by May he was secretary of war. During the Revolution and the years that followed, a cohort of loud, self-aggrandizing men—all of whom believed they were born to command—pursued agendas of their own that undermined the authority of military and political leaders like Sam Houston.

Fronteras: Your book is not only focused on reexamining myth and well-known historical figures but also on uncovering facets of everyday life that illustrate the effects of war and hardship on early Texas society. Your focus on Mary Maverick, the wife of Sam Maverick, a notable land baron and signer of the Declaration of Texas Independence, is particularly memorable. Why did you pick Mary Maverick to help you tell the story of Texas?

Sam Haynes: Sam Maverick is hardly an unknown figure in Texas history—UTA’s mascot is named after him, after all—but I was drawn to include the family in the narrative because of his wife, Mary, who was one of the first Anglo-American women to settle in San Antonio. Her diary and letters offer a poignant and revealing window into the world of unremitting loneliness and hardship that all women experienced on the western frontier. It was a dangerous and often violent world—she lost four children to disease and witnessed the grisly horror of the Council House Fight, a pitched battle between Comanches and Texas troops on the streets of the town that left dozens dead in 1840. At the same time, she was a complex and not altogether sympathetic character, a woman who, like all of us, possessed both flaws and virtues. She often had snarky things to say about her Mexican neighbors, and her comments on the enslaved people in her own household do not present her in the most favorable light. I wanted to include her in the narrative because she is much more than the archetypal “pioneer woman,” but rather a multidimensional and deeply human figure.

Zavala has always been viewed by Texas historians as a rather peripheral figure, but his long-standing rivalry with Santa Anna is crucial to understanding why the Mexican government responded to the crisis in the way that it did.

Fronteras: You have been reading, writing, and teaching about Texas for decades, so you knew a lot when you sat down to research and write this book. Can you share one or two surprising insights that grew out of your research for this new book, or any archival discoveries, that changed or shaped your arguments?

Sam Haynes: Thanks for asking this question! So much has been written about the military side of the Texas Revolution—from the siege of the Alamo to San Jacinto–that I wasn’t sure there was anything new to say. But here again, a wider lens is absolutely essential in order to draw a complete picture of what’s really going on. Texas historians have simply assumed that an Anglo insurgency caused Santa Anna to launch an ambitious offensive campaign in the winter of 1835/1836. In fact, preparations for the campaign–the largest military operation ever conducted by the Mexican government up to that time–were already underway in the fall of 1835, when the American community was still largely undecided as to what course it would take. Mexican federalists, on the other hand, had been talking about making Texas a beachhead of their operations to overthrow the centralist regime for months. Santa Anna had never heard of William Barret Travis, but Lorenzo de Zavala, his staunchest critic, arrived in Texas in June, and it was this news that prompted the government in Mexico City to act. Zavala has always been viewed by Texas historians as a rather peripheral figure, but his long-standing rivalry with Santa Anna is crucial to understanding why the Mexican government responded to the crisis in the way that it did.

This might seem like a minor point, but it really underscores how, once again, Anglo historians have always been laser-focused on the actions of white Texans, and in so doing lost sight of the bigger picture. There’s a reason why the Texas Revolution resonates with white Americans, and why the Alamo enjoys such a prominent place in the American historical consciousness—we’ve made the story all about us! So I guess this brings me back to the point I made at the beginning. To limit our study of Texas to a few Anglo men only tells us part of the story. By adopting a wide lens, however, a fuller–and, in many ways, richer–picture of Texas in the early nineteenth century comes into view.

Image credit: Cover tile designed by Christopher Conway.