As any serious student of Texas history knows, the European settlement of Texas can be traced back to the imperial rivalry between the Spanish and the French in the late seventeenth century. In February 1685, a French expedition under the command of René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, washed up on Matagorda Bay after an unsuccessful attempt to find the mouth of the Mississippi River. Building a crude stockade, Fort St. Louis, La Salle and his men would spend the next two years exploring East and Central Texas until his murder by a disgruntled member of the expedition. The settlement was abandoned soon afterwards, but news of La Salle’s misadventure greatly alarmed the viceroy of New Spain, who was determined to prevent the French from gaining a foothold in the Gulf of Mexico.

Enter the Spanish adventurer and explorer Alonso de León, who was ordered to find and destroy La Salle’s Texas settlement. Signs of a French presence along the Gulf Coast were hard to come by, however, and after two expeditions de León had managed to uncover scant evidence that the French had been there at all. In the spring of 1689, de Leónembarked on a third mission, marching into Texas with more than one hundred troops, and near Lavaca Bay discovered the ruins of Fort St. Louis. Pushing north into East Texas, de Leon encountered the Hasinai Indians, staying long enough to choose a site for the first Catholic mission in Texas, San Francisco de los Tejas.

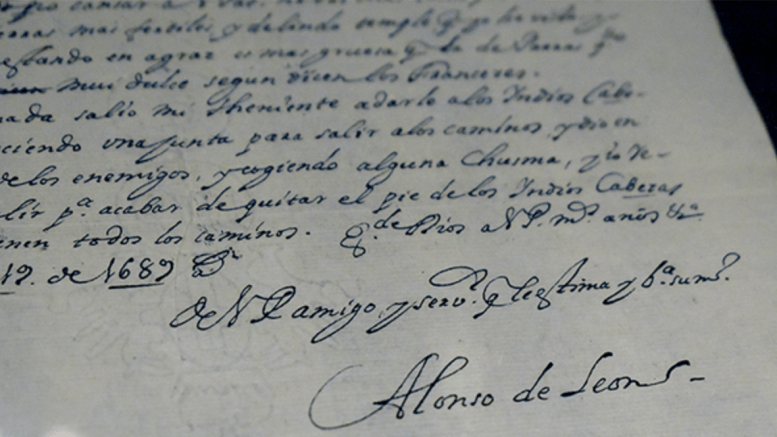

Returning to Coahuila, de León described his latest expedition in a letter to a Jesuit priest, Father Juan del Rincón. Never before published, the letter was recently acquired by Colorado map collector Wes Brown, who donated it to UTA’s Special Collections because of its great value to Texas history. The letter has now been translated by Modern Languages professor Sonia Kania.

The de León letter offers the first eyewitness account of La Salle’s ill-fated expedition. “It was a pity to see the quite considerable ruin that (had) befallen the settlement,” de León writes of the abandoned fort. “For there had been a smallpox outbreak in which 100 French died… The few that remained alive were killed by the Indians months ago, along with two friars and clergymen.” The letter is also important for its detailed account of the Hasinai Indians, who in the late seventeenth century were part of the great Caddo confederacy that extended into Louisiana and Arkansas. De Leon describes nine towns, each with as many as 800 homes. “They are very courteous people, and they cultivate a great deal of corn, beans, squash watermelon, and melons.”

Another remarkable feature of de León’s letter is its apparent reference to the famed “Lady in Blue.” More than a century and a half earlier, a Franciscan nun, María de Jesús de Agreda, who had never left her village in northern Spain, claimed to have been transported by angels to New Mexico and Texas, where she taught the Jumano Indians the gospels. And, incredibly, the Jumanos confirmed this. According to de Leon, the Caddos had received similar visitations. He writes: “for many years a woman used to come to see them and teach them, but she stopped coming a long time ago.”

Although De León related the findings of his expeditions in a memoir that has been available to scholars for many years, his letter to Father Rincon, dated May 19, 1689, is one of the earliest Spanish accounts of the region we know today as Texas. “This highly significant letter ranks alongside many other “foundational documents” of the state’s past, according to Special Collections archivist Ben Huseman, and is just “one of the many reasons that make UTA’s Special Collections such a great place to study its early history.”